Team Effort: Five Grinnellians Co-Author Paper on the Zebrafish Liver

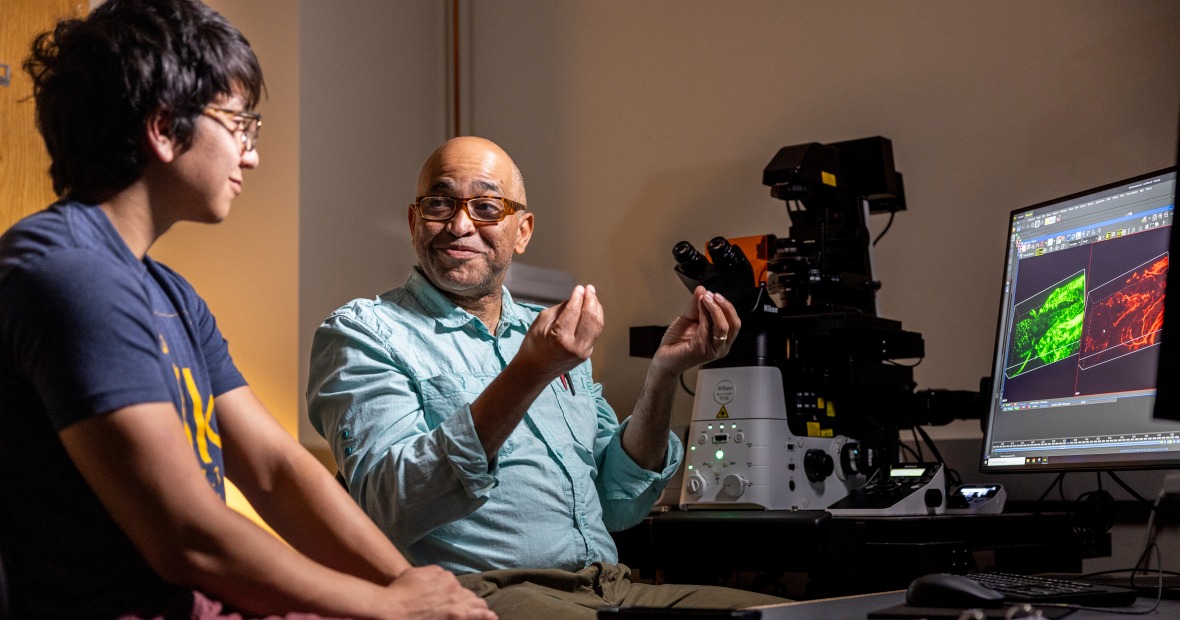

It’s a big deal when an undergraduate student is the primary author of a research publication. That’s why Pascal Lafontant, professor of biology, is proud to have his name listed after not one, but four, Grinnell alums on a paper recently published in Zebrafish.

With Lafontant and his collaborator at Massachusetts General Hospital, Juan Manuel González-Rosa (now at Boston College), Hayden Bhavsar ’24, Zoe Robinson ’23, Matthew Benson ’22, and Feven Getachew ’24 co-authored the paper presenting new molecular tools for other scientists studying liver development and regeneration.

What began as a summer side project in 2020 grew into a yearslong collaborative study in the Lafontant laboratory. Now, in “Lectins as Effective Tools in the Study of the Biliary Network and the Parenchymal Architecture of the Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Liver,” these Grinnell scientists are sharing their findings.

The Wide World of Zebrafish

When Lafontant first joined the faculty at Grinnell, he didn’t just bring a new area of expertise as a regenerative biologist. He also introduced a new model organism to the department: zebrafish. At the time, a storage room in the Noyce Science Center was converted into an aquatic lab to house his hundreds of fish. The small, translucent larvae and colorful adults share many genes with humans, making them a powerful model for studying development and disease.

These days, the storage room-turned-lab sees a lot of foot traffic. Lafontant mentors nearly 10 students each year in cellular and developmental research with zebrafish. While his primary focus is heart degeneration and heart development, he’s always encouraged his students to pursue the questions that interest them. “This kind of openness has led to all sorts of projects,” says Lafontant. “We’ve asked questions related to limb development, neuron development, and, most recently with Hayden, the zebrafish liver.”

Bhavsar conducted a Mentored Advanced Project (MAP) student in the Lafontant laboratory between his first and second years. “We were balancing all these different projects, and I was especially interested in this new side project with lectins and the liver,” Bhavsar recalls. He would go on to work on that little “side project” for the next three years.

Follow Your Heart (or Liver)

With Lafontant, Bhavsar’s goal was to identify what — if any — lectin proteins might be useful for labeling tissues in the zebrafish liver and its adjoining ducts.

What are lectins? They’re a class of proteins that bind only to specific carbohydrates. There are many lectins in nature — the Lafontant laboratory worked with tomato lectin and wheat germ lectin, for example. Because these naturally sourced proteins bind so precisely to only certain types of carbohydrates, they can also be a helpful laboratory tool.

About a decade ago, Lafontant and his students studied whether certain lectins might be useful in identifying types of zebrafish heart tissue. That project led to the development of better techniques for other researchers working with the zebrafish heart.

In 2020, Lafontant’s colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital reached out to ask him to explore lectins again — this time, in the zebrafish liver. When Lafontant brought the project idea to his MAP students, Bhavsar was all in. “It was very different work than what we had been doing in the lab,” Bhavsar reflects. “And generally, in zebrafish, the heart is more studied than the liver, so this seemed like an area where we could make some real contributions.”

A Collaborative Effort

Bhavsar continued his liver research with Lafontant the following academic year, and as other students joined the laboratory, the lectin project grew into a team effort. “That’s just how Professor Lafontant’s laboratory is set up,” explains Bhavsar. “It’s very collaborative. We’re constantly helping each other out with our projects.”

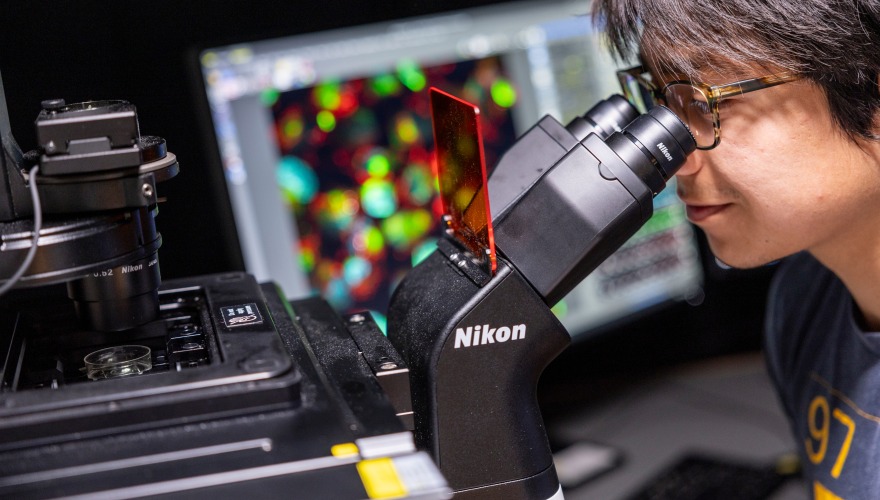

Which is how Getachew found herself taking a break from research with the zebrafish pectoral fin to help Bhavsar capture images of fluorescent tomato lectins binding inside zebrafish bile ducts. Of the 12 plant-based lectins that the team had tested for affinity to liver tissues, tomato lectin was the most promising.

Soon, Bhavsar and Getachew began to shape their findings into a paper. The writing process was simultaneously difficult and gratifying. As the team drafted the paper, it was often necessary to run further experiments or gather additional snippets of data to support their findings. “What we do in the lab is so much fun, but if you can’t take the data and make it presentable, it doesn’t mean much,” Getachew explains.

‘A Welcome Challenge’

Students in the Lafontant laboratory spent nearly a year procuring the additional data and thinking proactively about what information reviewers of the paper might look for. “Anticipating the kinds of question that reviewers might ask, understanding who your audience is, trying to get at all of that early on — it was a challenge,” Getachew says. “But it was a welcome challenge.”

“It is an amazing opportunity that we got to go through the paper review process as an undergraduate. That’s an experience that lab reports and coursework can’t quite capture,” Bhavsar adds.

Robinson and Benson completed MAPs in Lafontant’s lab and contributed experiments to the project but graduated prior to the paper’s publication. Robinson is currently pursuing her Master of Public Health degree at George Washington University, and Benson is in medical school at the University of Michigan. For Bhavsar and Getachew, who graduated from Grinnell this spring, the paper’s publication is the perfect finale to their years of research with Lafontant.

Bhavsar begins his training as a Ph.D. student at the University of Washington this fall, while Getachew will be working in an immunology lab at Boston Children’s Hospital. Both say that Lafontant has set their expectations of mentors exceedingly high. “It’s kind of scary to move to a different place and have a different mentor,” says Getachew. “I hope to work with someone who is half as good as Professor Lafontant.”