How We Write About Reproductive Failure

Funded by a Faculty Scholarship Competitive Grant, Gina Schlesselman-Tarango spent two weeks at Harvard University archives studying how the conversation around fertility and miscarriage has evolved in influential texts written by and for women.

Schlesselman-Tarango, associate professor and science librarian at Grinnell, studies gender and racial dynamics within “information work” — that is, the work that individuals must do to access, share, or create information. She’s particularly interested in the information work that surrounds infertility and pregnancy loss; challenges she refers to as forms of “reproductive failure.”

“From researching medical options, to charting your menstrual cycle, there is so much work that people struggling to conceive or give birth are expected to do,” Schlesselman-Tarango explains. “I’m interested in what texts people go to for that information, and how those texts have evolved over time.”

Excavating ‘Our Bodies, Ourselves’

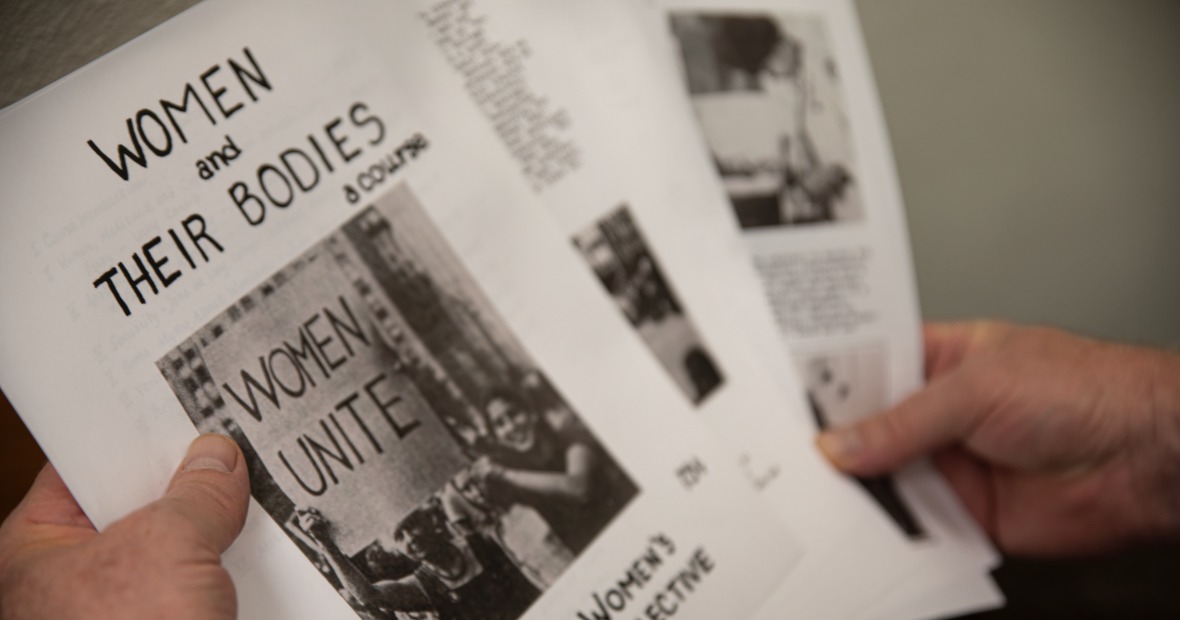

In Boston, Schlesselman-Tarango sought to explore the records of the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, the grassroots group that published the first edition of the groundbreaking medical text Our Bodies, Ourselves in 1970. Aiming to fill the existing knowledge gap and to empower women with accurate information about health, sexuality, and reproduction, the Collective published nine total editions of Our Bodies, Ourselves over four decades.

“The Boston Women’s Health Book Collective created this incredibly important text for women through an explicitly feminist lens,” explains Schlesselman-Tarango. “Yet, for the longest time, fertility wasn’t considered a feminist issue. And so that’s why I was interested in what the Collective had to say about it. When did they start taking an interest? When things like IVF and reproductive technology came on the scene, how did they handle that in their text?”

In Boston, Schlesselman-Tarango split her time between the Schlesinger Library at Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute and the Center for the History of Medicine at Harvard Medical School’s Countway Library. These libraries house extensive records of the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective.

The Evolution of a Dynamic Text

In the Harvard archives, Schlesselman-Tarango perused everything from chapter drafts and early editions of Our Bodies, Ourselves to the materials that went into making the book: scientific studies, consumer health articles, and a large collection of letters from readers. “Through these letters, you could see what people felt about the book and what they felt was missing, and how that feedback was incorporated into later editions,” she explains.

As readers and scholars offered feedback, and as the scientific and medical fields evolved, so too did the content of Our Bodies, Ourselves. “One of the early critiques of the book is that it was very much focused on childbirth,” says Schlesselman-Tarango. “And so, you see in later editions that they begin to introduce more information about menopause, infertility and pregnancy loss.”

Having returned to Grinnell, the real work now will now begin for Schlesselman-Tarango; two weeks in the archives provided her with months’ worth of sources and information to analyze. “I am very excited to sift through what I found in the archives, to begin to pull out themes and arguments and think about how what I’ve found relates to these bigger questions I have about information work,” she says.

Already, she’s noticing a double bind that the topic of infertility seems to have placed on the Collective. “What I saw the Collective grappling with, especially as reproductive technologies became more mainstream and more of a feminist concern, was figuring out how to hold two things at once. That is, holding both a skepticism for the medical industry, which had historically overlooked women and their rights and well-being, and, I guess, a more traditional evidence-based medicine approach,” she explains.

Connecting Past to Present

Though the research is rooted in historic sources, Schlesselman-Tarango believes this project couldn’t be more fitting for the present day:

“Early in the feminist movement, there was some question as to whether infertility or reproductive failure more broadly was a legitimate concern. But I think that we’re seeing challenges to reproductive health and reproductive rights now, and it’s become clearer for more people that reproductive justice is a necessary lens with which to look at the threats to standard care for miscarriage and IVF that we've seen in the landscape lately,” she explains. “This project is a very good reminder that yes, infertility, and pregnancy loss are absolutely reproductive justice issues.”