Falling into Place

History course helps students understand Grinnell’s place in the world

You can learn a lot by looking at what people throw out — history might just be lying on the ground, waiting for someone to notice.

Evan Albaugh ’25 always notices.

When he saw construction workers tearing out the old pavement on Fifth Avenue, he couldn’t wait to sift through the exposed dirt, searching for artifacts of long-ago Grinnell.

Albaugh, a third-year history major from Ankeny, Iowa, looks for artifacts — shards of antique glass, old coins, etc. — wherever he goes. He says Grinnell has been a treasure trove of these cast-off everyday objects.

“People throw away really interesting things sometimes that I think do kind of reveal information about the society,” he adds.

Popping the Grinnell Bubble

In spring 2024, Albaugh found a course that encouraged his interest in local history, Historical Landscapes of Grinnell.

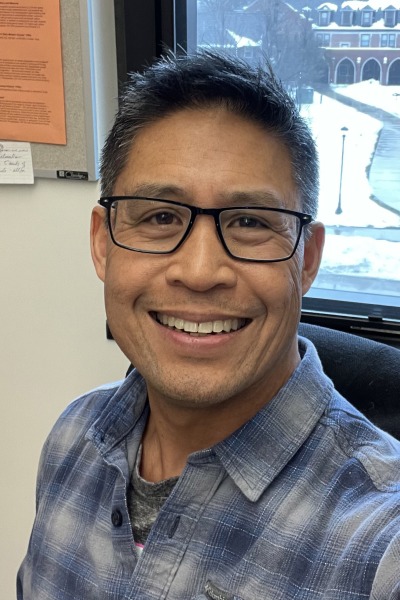

Professors Albert Lacson (history) and Cori Jakubiak (education) developed and team taught the course for the first time this year. Lacson says the 2022 racist incidents and vandalism in Grinnell inspired them to create the course.

“One of the surprising things was to hear the frustration and anger that this sort of thing happened here, as if Grinnell was somehow immune from national and international patterns,” Lacson says. He and Jakubiak developed the course to demonstrate that the College and town have been and still are connected to the larger nation and world.

Lacson cites Grinnell’s founding in the mid-19th century as an example. Anti-abolitionist sentiment in Davenport, Iowa, compelled then-Iowa College to move to Grinnell. There, the College and the town both became enmeshed in the issues that shaped the country in the years leading up to the Civil War. Community founder and abolitionist J.B. Grinnell and others made the town a stop on the Underground Railroad, helping enslaved people escape to freedom.

“That’s the starting point for this town,” Lacson says.

Connecting with the Community

Jakubiak says she and Lacson envisioned a course that would help students engage with place. As director of the Center for Prairie Studies, she thinks a lot about place, sustainability, and community.

Why is place so important? “I think for many students, Grinnell feels placeless,” Jakubiak says. “I really want students to engage with why Grinnell is the way it is, rather than writing it off as nothing.” She hopes students will think about not only what’s here now, but also what was here in the past.

“Students were shocked to see old pictures of the hotel that used to be right next to Central Park, with just a load of pedestrian traffic crossing from the train station,” she adds.

Jakubiak also wants to avoid a situation in which students graduate from Grinnell and leave without considering Grinnell as a place in its own right. She hopes they will learn to see not only what the College can do for them, but also how can they learn to see the place, to see different kinds of people, and to ask different questions.

“It’s a way to also build community that’s important,” Jakubiak explains.

Lacson agrees. “We thought it could be really useful for both the College and the town to have students connect with people from the town through a shared history,” he says.

Histories Matter

It’s often said that history is written by the victors. “But the truth is … we all get a say,” Jakubiak explains.

She and Lacson want students to understand that history isn’t just made by the famous people, the leaders whose names are in every history textbook. Everyone plays a part, and understanding that truth offers a way for students to make meaningful connections with the people in the town, Lacson explains.

“Through helping people see that, wow, the family stories that their great-grandparents told their parents, and their parents told them, and stories that are connected to these material objects,” he says. “Hopefully we can play a role in convincing people that their personal histories matter.”

Lacson adds, “I like to think that we succeeded in helping students realize that not just Grinnell, but hopefully every place they go to, they’ll begin to see connections that they may not have seen before taking the class.”

Perspectives on Place

Students in the class heard from a diverse list of guest speakers. That diversity was a deliberate choice, Jakubiak says. “It was a really wide variety of speakers, and in that sense, a lot of different kinds of knowledge.”

The speakers included representatives of the Poweshiek History Preservation Project, the Iowa Lincoln Highway Association, University of Cincinnati public history program, the Iowa Geological Survey, the Neal Smith Wildlife Refuge, the nearby Meskwaki Nation, and others.

Lacson particularly wanted students to hear from the Indigenous people upon whose land Grinnell College stands. “We did think it was very important for our students to connect with those for whom this history matters, whose lives revolve around preserving and understanding the history of this region,” he explains.

“That’s one of the biggest things we wanted students to be able to grapple with — that what they see here right now hasn’t always been here,” Lacson says.

Experiencing Grinnell

But some things endure. The sky, the wind, the grass, the trees — these have always been here.

Jayson Kunkel ’26 wandered through Summer Street Park, looking up at the cloudless blue sky. A breeze ruffled the maple leaves overhead, and he noticed masses of helicopters, almost ready to spin to the ground. A woman walked by with two dogs. On the banks of a small creek, Kunkel heard a frog splash into the water.

Kunkel, a computer science and anthropology double major from Des Moines, chose the park for his “Sit-Spot” assignment, one of several ways students in the class explored the concept of place. They were asked to choose a place on campus or in the community and visit it 10 times during the semester, observing and experiencing it. Their reflections became blog posts for the class website.

Kunkel’s Sit-Spot reflections exceeded expectations, Jakubiak says. He started out sitting in one place, observing the flora and fauna. By the end of the semester, he had ventured to every corner of the park. He even participated in a community clean-up project there.

“His project was a fabulous example of how he came to care about a spot by returning to it over and over,” Jakubiak says.

Grinnell in the Wild

Another assignment, “Grinnell in the Wild,” asked students to seek out smaller, more hidden places to research and explore. Albaugh’s Grinnell in the Wild project focused on some of the artifacts he’s found around Grinnell, both on campus and in town.

“Anywhere where there was exposed soil, there were things that were just sitting there that nobody else looked at or picked up,” Albaugh says. He especially likes antique bottles and glass shards, but he also found coins and all sorts of metal artifacts. His blog posts provided detailed information on the objects, illustrated with close-up photographs.

Digital Storytelling

The final project, “Histories of Grinnell,” asked students to use a digital platform — blog posts, ArcGIS Story Maps, etc. — to share the results of their research while telling a compelling story and creating a digital record of their discoveries.

Students were required to conduct an interview with someone familiar with their topic. These interviews brought history to life in a way that other forms of research cannot, Jakubiak says. “History is not something old and dusty in a textbook to be fought over,” she says, “but something alive in the present that we can all contest and weigh in on.”

Evelyn Dziekan ’24 and Jayson Kunkel both chose the Old Glove Factory for their final projects. The building was home to one of Grinnell’s first manufacturing companies, Morrison-Shults Manufacturing. After the company closed, the Old Glove Factory stood empty for several years before the College bought it in 1999. An award-winning renovation created a space for some of the College’s administrative offices.

A biochemistry major from the Chicago area, Dziekan says she loved this class, which was her first history course. “I wanted to learn more about Grinnell as a town,” she says.

Kunkel agrees. He has always had an interest in local history, and this class amped up his interest. “It just opened my eyes to so many things I didn’t know,” he says.

Together, he and Dziekan interviewed Frank Shults, the son of Frank Shults Sr., who had worked at the Morrison-Shults Manufacturing Company when it was an active manufacturing enterprise. “He was able to tell us a lot about the inner workings of the factory,” says Kunkel.

He believes the Old Glove Factory is a unique space that helps bridge the town-gown divide. “The fact that it is owned by the College and it’s such an old landmark in town — I think really ties both entities together,” Kunkel says.

When Past Resonates with Present

Stella Lowery ’24, a studio art major from Brooklyn, New York, stayed on campus for her final project. “I was really interested in the additions that are built on buildings on campus,” she explains. “I was looking at how the campus culture shifted from utilizing the Forum and Burling to using the HSSC and JRC.”

Lowery interviewed a local alum and used the Grinnell Digital Archives in her research. She especially enjoyed poring over old copies of The Cyclone yearbook. “I just got totally distracted by the yearbooks almost instantly,” Lowery recalls.

She appreciated learning about what Grinnell was like in the past, which often resonated with her own experience in the present.

“To focus on that through the lens of a physical space has been really interesting,” Lowery says.

One Man’s Garbage

Lacson and Jakubiak likely didn’t expect anyone to choose the garbage of Grinnell as a final project, but they were thrilled when Albaugh proposed it.

“I thought it was super creative, brilliant way to try to understand the changing history of this place,” Lacson says.

“Garbage disposal isn’t necessarily the most glamorous thing, but it fits really well with my interests in especially untold histories and also things that are left behind,” Albaugh says. He believes garbage deserves to be studied as a part of the community’s larger history — albeit often a hidden one.

Once it’s at the dump or landfill, garbage might be out of sight, but that doesn’t mean it’s gone. “It all has to go somewhere,” Albaugh says. “The things that were thrown away by Grinnellians 150 years ago — many of the non-organic materials are still intact in the ground somewhere.”

A Deeper Connection

Lacson calls this iteration of Historical Landscapes of Grinnell the “first draft” of the course. He and Jakubiak are already planning the next offering, which will explore even more aspects of place and local history.

Lacson says that creating a partnership between a historian and an educator to teach a course such as this taps into a rich vein of knowledge and diverse perspectives, while also fostering mutual respect.

Jakubiak agrees. “Team teaching is … a really great area for faculty growth, professional development,” she says. “We’ve been colleagues and friends for a long time, but to see someone teach is really different.”

They both share a personal interest in the subject matter. “We’ve both had an interest in place, and specifically this place,” Lacson explains. “We wanted to use this as an opportunity for us to deepen our connections to this place.”

Albaugh says that the class also gave him a greater appreciation for the town of Grinnell. “I think we addressed some really systemic issues of this disconnect between the town and the College,” he says. “Learning more about the town and learning to appreciate it for what it can offer has been really nice for me.”

Vivero: Exploring and Cultivating New Ideas

Historical Landscapes of Grinnell was a class supported by Ohana Sarvotham ’25 and Kailee Shermak ’25 of Grinnell’s Vivero Digital Fellows Program, which combines technology and scholarship to create a digital liberal arts community at the College.

Since 2017, the Vivero program has expanded the reach and bounds of academic study and research at Grinnell. “At the heart of Vivero is a goal of diversifying the field of digital scholarship and digital liberal arts scholarship,” says Tierney Steelberg, co-leader of the program.

Sponsored by the Grinnell Libraries, the Digital Liberal Arts Collaborative, and the Center for the Humanities, Vivero embodies the College’s commitment to social justice, diversity, and excellence in undergraduate liberal arts education.

The class also received support from Humanities in Action, a grant to the College from the Mellon Foundation that helps faculty members create new courses that actively illustrate how the humanities prepare Grinnell students for lives of reflection, growth, and action